I recently published a brief history of radio’s early days — from Marconi’s stunts to the rise of broadcasting twenty years later — in Make: Magazine.

The first two decades of radio were a whirlwind of invention, competition, and drama. And the amateur radio operator ended up the hero of the story.

Radio was a defining technology of World War I. The military found a use for the tool in frontline communications, as well as for the legion of amateur radio operators who joined the war effort. But beyond the battlefield and the maritime applications, the technology struggled to find its footing. It took years of amateur experimentation to discover the rightful place of radio as a broadcasting tool.

Throughout the first decade of radio, Marconi, De Forest, and the inventors-turned-entrepreneurs were busy trying to grow their businesses. That meant finding customers who would pay for their services. The Navy was one. Marconi and others were also trying desperately to disrupt the existing communication business of the time: the telegraph. They thought their technology was replacing the telegraph and the telephone — a new form of one-to-one communication. While they were busy analyzing what the business was, they failed to imagine what the technology could become.

The bureaucracies — corporate and military — dismissed the amateur operators, even as their numbers swelled and the hobby boomed. But the amateurs were prototyping the cultural use of radio. The phenomenon was emergent. “Listening in” to broadcasts became a popular activity. People were curious about how other people were living and radio became a window into a new world.

By 1922, companies and newspapers began to catch on. Broadcasting was here and it was going to be huge. It was an overnight success two decades in the making. Herbert Hoover, then U.S. Secretary of Commerce, organized a conference to promote and understand this “astounding” development in American society. The rest — the rise of broadcasting and its influence on our modern world — is now history, even as the role of the amateur is less well known.

It’s a relevant story to revisit because of the similarities between the early years of radio and the current Large Language Model (LLM) craze.

Corporate Oversight

By 1920, all the meaningful radio patents had been scooped up by the big corporations: AT&T, General Electric, RCA, etc. They thought radio posed a threat to their current business — the telegraph and telephone — and sought to head off competition. They knew the radio could be important, but were unsure how to sell it.

Amateurs had no such inclination. They were eagerly building up their tools and skills without the pressure of customer demand. Frank Conrad, a Westinghouse engineer who had set up an advanced amateur station in his garage outside of Pittsburgh, began a weekend broadcast with his friends where he would play music and records for anyone within listening distance. In a eureka moment, his boss happened to overhear the broadcast and see an advertisement for amateur wireless sets in the local newspaper. Suddenly, the future of radio came into view for the corporates. Broadcasting was here and it was going to be huge.

In her book, Inventing American Broadcasting, 1899-1922, Susan Douglas refers to this unsung amateur leadership as the "social construction" of radio. They found a latent desire among people who wanted to simply “listen in” – the first broadcast network and audience. They had taken the technology into the wild, and “embedded radio in a set of practices and meanings vastly different from those dominating the offices of RCA.”

Although we’re still at the starting gate for LLMs, it already feels like a corporate story, with all the big research teams and necessary compute tethered to Google and Microsoft. And the corporates seem obsessed with positioning LLMs as the future of internet search — the business they know.

Meanwhile, street use is totally different. The bizarre new art projects. The quirky poems. The disturbing conversations. There’s something there, but it doesn’t feel like searching.1

Transformers, the discovery behind the recent advances in AI and LLMs, have been around since 2017 after a group of Google engineers published the paper “Attention Is All You Need”. Researchers have known about their efficacy and shortcomings for years, and transformers have steadily become ubiquitous in machine-learning applications. But we’ve entered a new chapter with the open release of models like Stable Diffusion and the accessibility of ChatGPT — the tools are firmly in the amateur’s hands now. It’s finally gotten personal.

It all seems eerily familiar to the situation a century ago, when AT&T, RCA, and journalists thought radio was simply a wireless telephone.

The current headlines are all trending toward corporate battles, AI safety, and prophesizing about how AI will disrupt existing business models — all interesting and important topics. But the real story right now is the playing around. It’s pathfinding work. Personally, I’m more interested in the wild dreamscapes that people are publishing than I am in Bing.

But what about the scary stuff?

Many smart people have published criticisms and worries about the civilization-ending downsides of AI. I find most of them interesting — and frightening — but not particularly useful.

I don’t have anything productive to add to that debate, except to point out the popular narratives during the initial broadcasting boom.

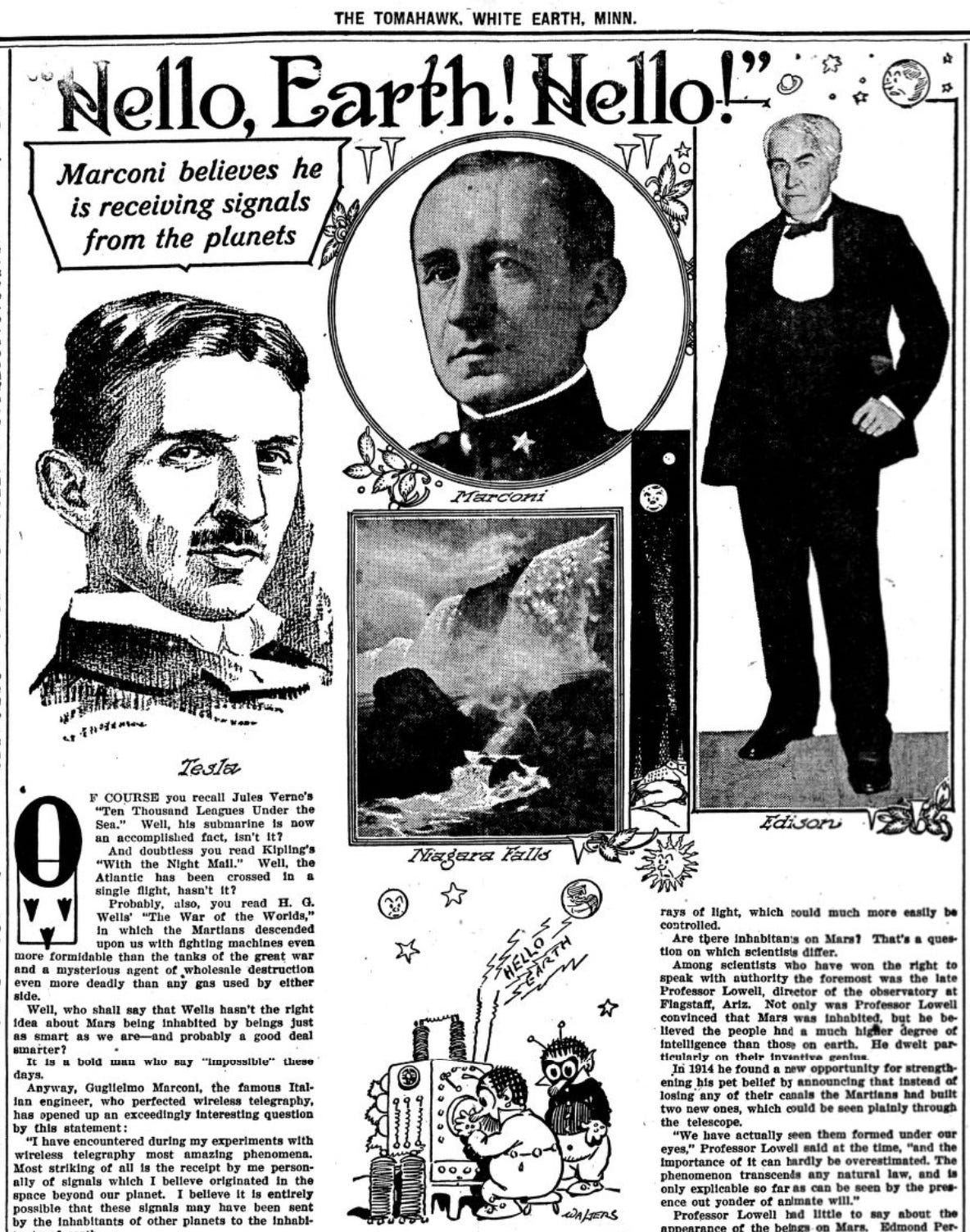

Every time a technology races ahead of our comprehension — when it surprises us and leaves us disoriented — we come up with fantastical explanations for what’s coming next. For radio, the most extreme visions came from the creators. Almost immediately, Nicola Tesla and Guigliomo Marconi were convinced that they were receiving radio signals from outer space. Tesla, in particular, was convinced it was coming from Mars.

Although it seems outlandish now, this was a mainstream opinion by serious people. The headline and subtitle of Current Opinions2 coverage of Tesla’s theory:

That Perspective Communication with Another Planet: Nikola Tesla Enters Into the Subject from the Practical Standpoint

According to Douglas, almost all of the journalistic coverage of radio in the early 1920’s went to extremes with their predictions. They spoke of a coming cultural unity and understanding, a revolution in education, and even a more informed and reasonable political environment. The possibilities were endless.

The perils and concerns were there, too. The musicians, of course, were unhappy about the sound quality. But the biggest fear was that radio wouldn’t live up to its educational and democratizing potential.

In the end, the predictions about radio turned out to be directionally correct, but the extremes were too extreme. The fears were justified but mostly misplaced. The promise and hope were subdued by a sort of banality — the new eventually became the new normal. Radio turned out to be a scaled-up, corporate-driven version of the original amateur broadcasts. It was all right there at the beginning, buried beneath the hype.

I’m the last person who should be making predictions about LLMs or AGI, but I do wonder if it is, again, all right here: the bizarre images, the poems, and the instant marketing copy. Maybe that’s it. While everyone debates and worries, the amateurs are showing us the future yet again.

Robin Sloan made this point better than I could.

I find these articles amazing. If I hadn’t gone back to the archives, I would have doubted the seriousness of these predictions.

“WHEN the brilliant electrician, Nikola Tesla, was informed by a newspaper reporter some weeks ago that William Marconi had received strong wireless signals seeming to come from beyond the earth, something like corroboration resulted. Nikola Tesla, as he is quoted in the New York Evening Post, remembered that years ago he recorded extra-planetary signals in his laboratory at Colorado Springs. These extra-planetary signals were barely perceptible at the time, but their measured regularity was such that they could not, in Tesla's opinion, have been accidental static disturbances. They possessed order. Mr. Tesla admits that he could not say with certainty that they came from Mars, altho, as quoted in the New York newspaper, this remains his belief. In our solar system, he adds, Venus, the earth and Mars represent respectively youth, full growth and old age.”