Right-Sized Ambition

Going big by starting small.

Did you know you can order a human skull on the internet?

I learned that, along with a host of other interesting facts, by attending a presentation by a team of engineers and scientists who are trying to develop a new type of non-invasive brain-computer interface. The skull was a critical tool for the team to assess the viability of their proposed technique.

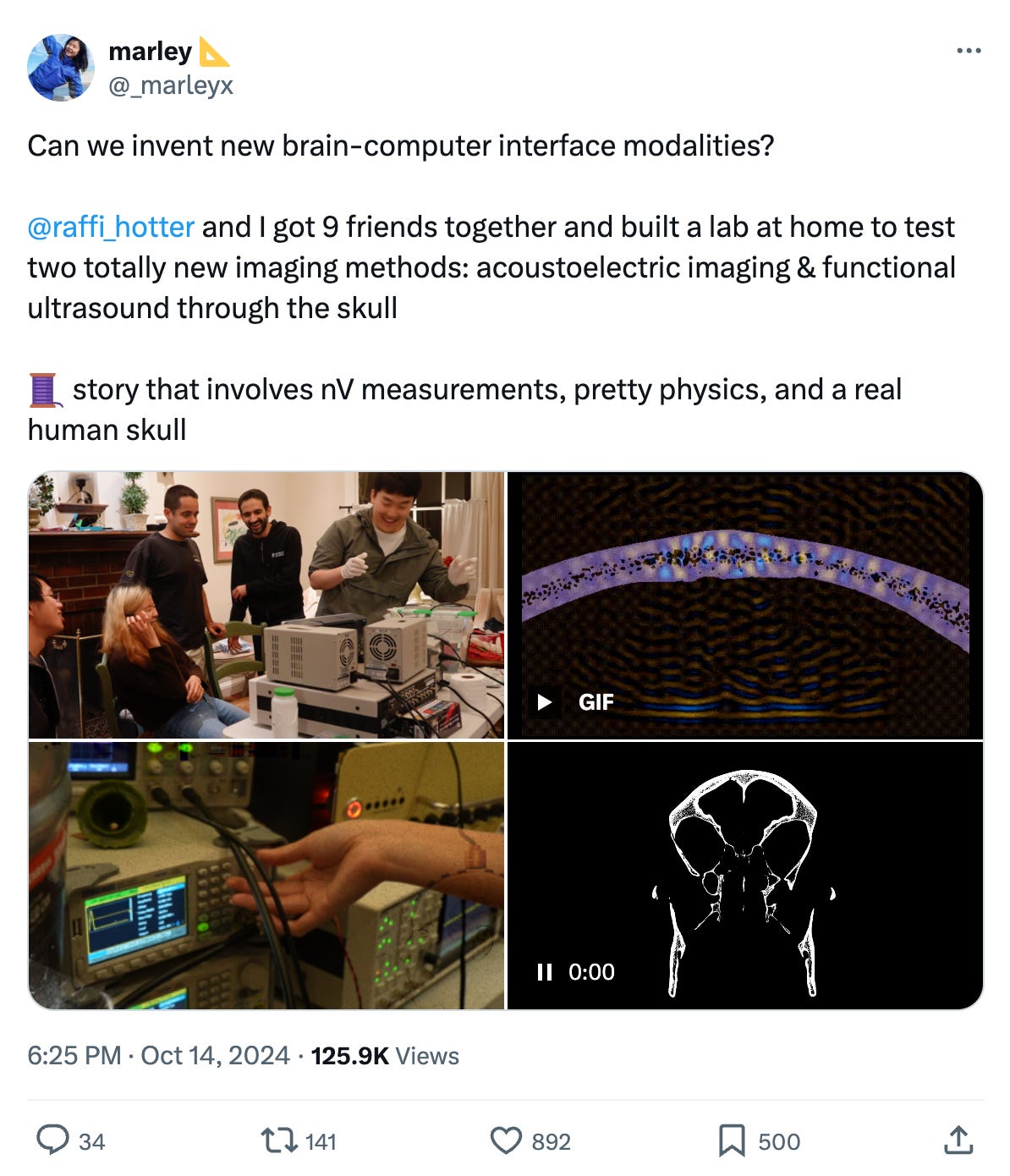

It would be impossible for me to tell the story better than Marley and the team already did in their entertaining thread on X:

To sum it up: a group of friends and collaborators rented an Airbnb for a focused period of hacking and work. Their goal was to test the possibilities of two new brain imaging methods using an acoustoelectric strategy and another using functional ultrasound.

I had been paying attention to neuromodulatory ultrasound after reading Sarah Constantin's compelling series on the topic. The ability to non-invasively interact with precise regions in the brain appears full of both research and therapeutic potential, so I was primed to notice Marley's post and story about the Airbnb experiments. Anytime I see a technology go from the research lab to the garage (or in this case: the Airbnb living room), I pay attention.

Meeting the team, and hearing their enthusiasm for the new questions they've discovered, gave me confidence that they're on an interesting path. I'm cheering for their ongoing experimentation. But this post is not about functional ultrasound, although I suggest you follow both the team and Sarah for further updates on the technology. Instead, the experience caused me to reflect on the nature of ambition and, more specifically, how far the technology community has drifted from what I call "right-sized ambition".

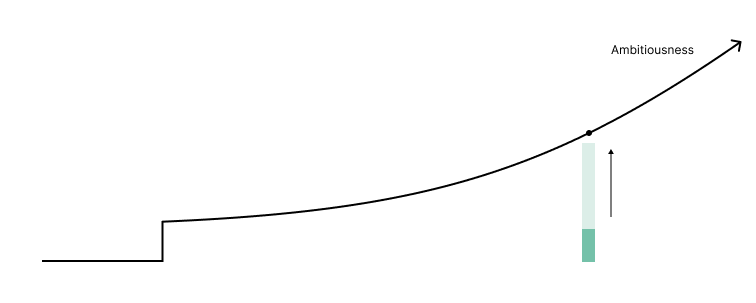

I made a few simple diagrams to explain.

The first is a rough sketch laying out the scale of ambition. The stark jump comes when you're making something. Before that, you're dreaming. In the earlier stages, there are prototypes and experiments, which progress steadily towards products or feats of discovery.

The first milestone should be the early prototype—the "wouldn't it be cool if..." experiment—that helps chart the course towards the next big question or goal.

I love this stage. This is exactly what Marley and the team achieved in the Airbnb: a goal just beyond the reach of their skills, resources, and know-how. The reason they were able to pursue the adventure was owing to a small grant from Protocol Labs who helped underwrite their equipment purchases. As you can see from the celebratory video in the X thread, this moment is FUN.

On the far end of the spectrum is a project of maximum ambition. From my perspective, and probably many others, the Starship booster tower catch is the most ambitious project in decades. Again, the goal was at the limit of the skills and resources of the SpaceX team to achieve. It was recently unimaginable, barely possible, and now, amazingly, a historic moment. As you can see from the celebratory room full of SpaceX engineers, this moment is also VERY FUN.

This is where the idea of right-sized ambition comes in. In some startup circles or non-profit prize efforts or best-selling thought leadership, there's an emphasis on "big bets" and highly ambitious projects, which is not a bad idea on its own. I'm all for the moonshots. But it should be noted—and I haven't seen anyone write this anywhere—that starting a moonshot from scratch and struggling to muster the resources together to do something of maximum ambition is NOT FUN.

Too often, the work turns into constant fundraising; chasing big donors or patrons and being tempted into making bigger and bolder claims. I've seen many good people get stuck on the speaking circuit, not for want of the spotlight (although sometimes that happens), but because they view publicity as the only way to achieve their goal.

Trying to close this gap can be painful:

Another way is to focus on scaling your ambition over time. Start with an ambitious-to-you prototype that demands further iteration and exploration. Don't worry about organizational structures or fancy pitch decks. Resist the temptation to formalize the effort—keep it a project for as long as possible. Be like Marley and the team.

Again, this is not a knock against the moonshots. By all means, if you can afford it, take a big swing. But know that there is another path—well-worn and productive—of right-sized ambition.

Many of your favorite ambitious projects started this way, even though those early stories don’t get the headlines. Starting small builds the confidence to go bigger. For every Waymo, there is a Stanley. For every SpaceX, there is a BFR. For every new non-invasive brain-computer interface, there might be a skull from skullsunlimited.com.

Note: I’ll be publishing several pieces in the coming weeks about small grants—lessons learned from three years of running a micro-grant program. I’ll also be announcing the next batch of grant programs from the Experiment Foundation. Stay tuned for that!